As we discussed in an earlier post, advancements in the understanding of cervical cancer and the invention of the HPV vaccine are inextricably intertwined with Black History Month (February). Why? Because the “HeLa cells” used in groundbreaking scientific research were from the cells of Henrietta Lacks, a young Black woman who lost her life to cervical cancer in 1951 and whose cell lines have transformed modern medicine.

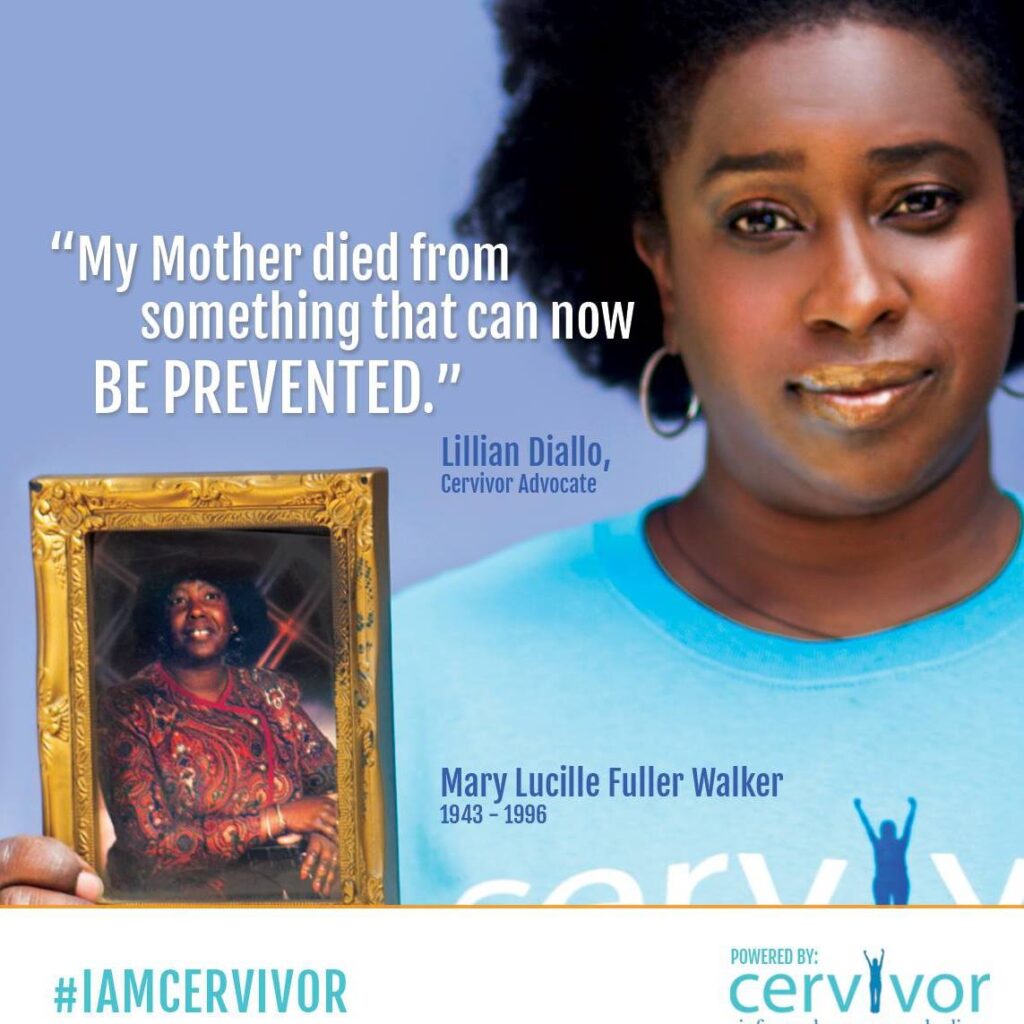

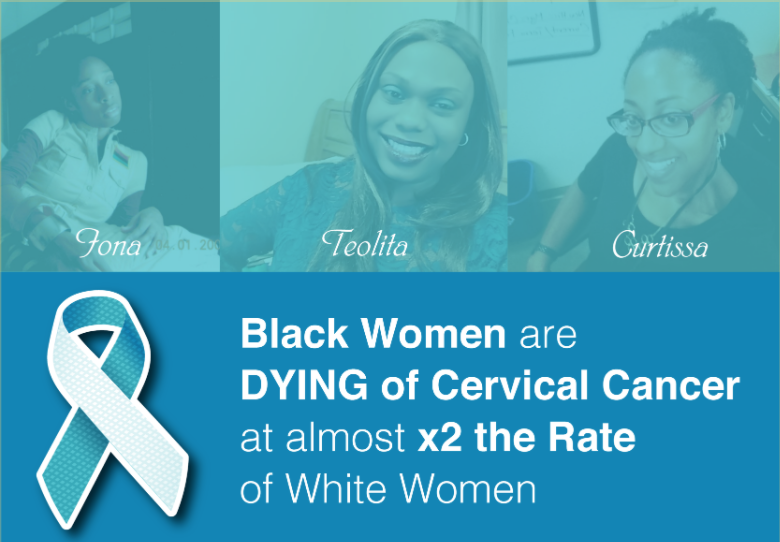

While HeLa cells were critical to the science that led to the HPV vaccines that have the power to prevent cervical cancer, today Black women in the U.S. bear a disproportionate burden of cervical cancer. Although cervical cancer occurs most often in Hispanic women, Black women have lower 5-year survival rates and die more often than any other race. In fact, they have nearly twice the cervical cancer mortality rate compared to white women.

Why?

Interestingly, while most women with cervical cancer were probably exposed to cancer-causing HPV types years before, on average, Black women do not receive a diagnosis until 51 years of age. That compares to white women who have a median age of cervical cancer diagnosis at 48. Those three crucial years could make the difference between a treatable versus terminal cancer.

Why?

Researchers have reported that due to social and economic disparities, many Black women do not have access to regular screenings. Screening programs often fail to reach women living in an inner city or rural areas because of lack of transportation, education, health insurance, primary care providers who can perform cervical cancer screenings, or availability of nearby specialists for follow-on care.

How can we make a meaningful difference?

The underlying causes of health disparities are complex and are multi-layers with lifestyle factors (obesity, cigarette smoking, etc.), socioeconomic factors (access to health insurance, access to healthcare providers), representation in research (clinical trials), and much much more. Yet there are still meaningful ways to make a difference.

Help increase screening rates.

Increasing screening rates could greatly reduce deaths from cervical cancer among Black women, Hispanic women and other underrepresented communities. This requires the delivery of interventions directly to underserved women such as screenings based at accessible locations closer to their places of residence – such as via mobile vans and/or screening locations at local community centers instead of medical clinics. This can substantially lower cervical cancer mortality rates through early detection.

The National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP) has programs – and importantly, partnerships – in place across states, territories and tribal lands.

For example, in South Carolina, NBCCEDP has brought screening to underserved communities in collaboration with nonprofits and faith-based groups including The Best Chance Network and Catawba Indian Nation. In Nevada, programs with Women’s Health Connection increased screening numbers by 30%. Connect with your state’s screening programs. Share info about local screening programs and events.

Encourage HPV vaccination

Encourage clinical trial participation

A lack of racial and ethnic diversity in both cancer research and the healthcare workforce is one of the major factors contributing to cancer health disparities, according to the American Association of Cancer Research. Clinical trials lead to the development of new interventions and new drugs. They are used to make better clinical decisions, but there is often a significant underrepresentation in clinical trials by non-White races and ethnicities. With a focus on targeted therapies and precision medicine, representation in clinical trials is increasingly important so that research includes and reflects all groups. Where to start? Share links to www.clinicaltrials.gov – where clinical trials are listed and searchable by location, disease, medicine, etc.

During this year’s Black History Month, let’s work together to change the history of cervical cancer.