Hey there Cervivor community!

My name is Kimberly Williams, I’m a recurrent cervical cancer survivor and Cervivor Patient Advocate that resides in the great state of Texas! I’m elated to join Team Cervivor as the Chief Diversity Equity and Inclusion (D.E.I.) Officer.

When I was diagnosed with cervical cancer in February 2018, it made me realize that being a mom to my two children, a double Master’s recipient in Management and Healthcare Management, and devoting 20-plus years to social services did not lessen my chance to get this diagnosis. The moment that I found out I had cervical cancer my focus shifted to desiring information concerning this disease that invaded my body.

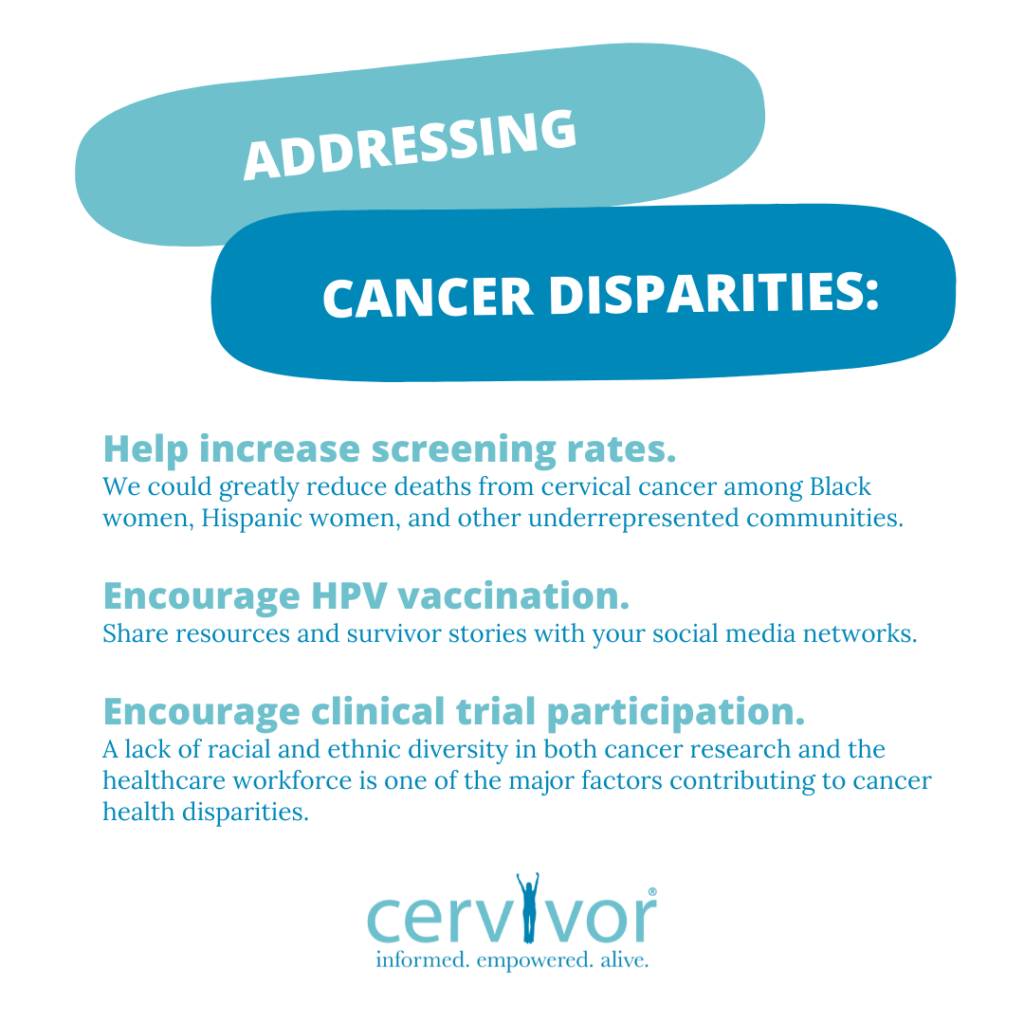

I was introduced to Cervivor by a Cervivor Ambassador in March 2018 after my radical hysterectomy. During this time I listened, watched, and learned from other Cervivors. I faced a recurrence of cervical cancer in 2019 which led me to advocate even more! I began to share my story with those within my reach (my community, my family, and my friends). That’s when I realized that my story as a Black cervical cancer survivor mattered. There was a diverse population who were not insured or underinsured, and not receiving cervical cancer screenings, but who were listening to my story and taking action. It became a mission for me to help these communities by providing support and knowledge, and also sharing my story.

In 2021, while participating in a Cervivor event, I found my voice and drive even more. I learned how to frame my message for different audiences. This brightened my light to make a difference in the underserved communities by sharing Cervivor’s mission through my story. In January 2022, I was in shock to be given the Cervivor Rising Star award. As I accepted the award I understood there were still grassroots efforts that needed to occur to reach those aforementioned communities.

In January 2022, I participated in the Cervical Cancer Summit powered by Cervivor. During this summit participants were encouraged to join the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network (ACSCAN) to work to impact our local communities and share our cancer stories. Based on this encouragement, I joined the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network of Texas as a volunteer, which opened doors for me to share my story during HPV awareness events at underserved elementary schools to parents inquiring about the HPV vaccine. I also was afforded the opportunity to share my story during an HPV Roundtable event hosted by the American Cancer Society. Throughout 2022, I continued to share my story at events because I truly understood that my story mattered.

In the summer of 2022, I was chosen as a patient advocate for NRG Oncology’s Cervix and Vulva committee that reviews concepts for clinical trials, which includes ensuring a diverse population participate in the clinical trials. In September 2022, Cervivor hosted their Cervivor School in Nashville, Tennessee and I was awarded the Cervivor Champion award. What a humbling moment in my cancer journey to be viewed as a “champion”.

As I pondered the word champion I found this definition, “a person who fights or argues for a cause” and I silently agreed. Yes, that’s me. That’s what this community stands for and Cervivor helped me locate that champion inside of me!

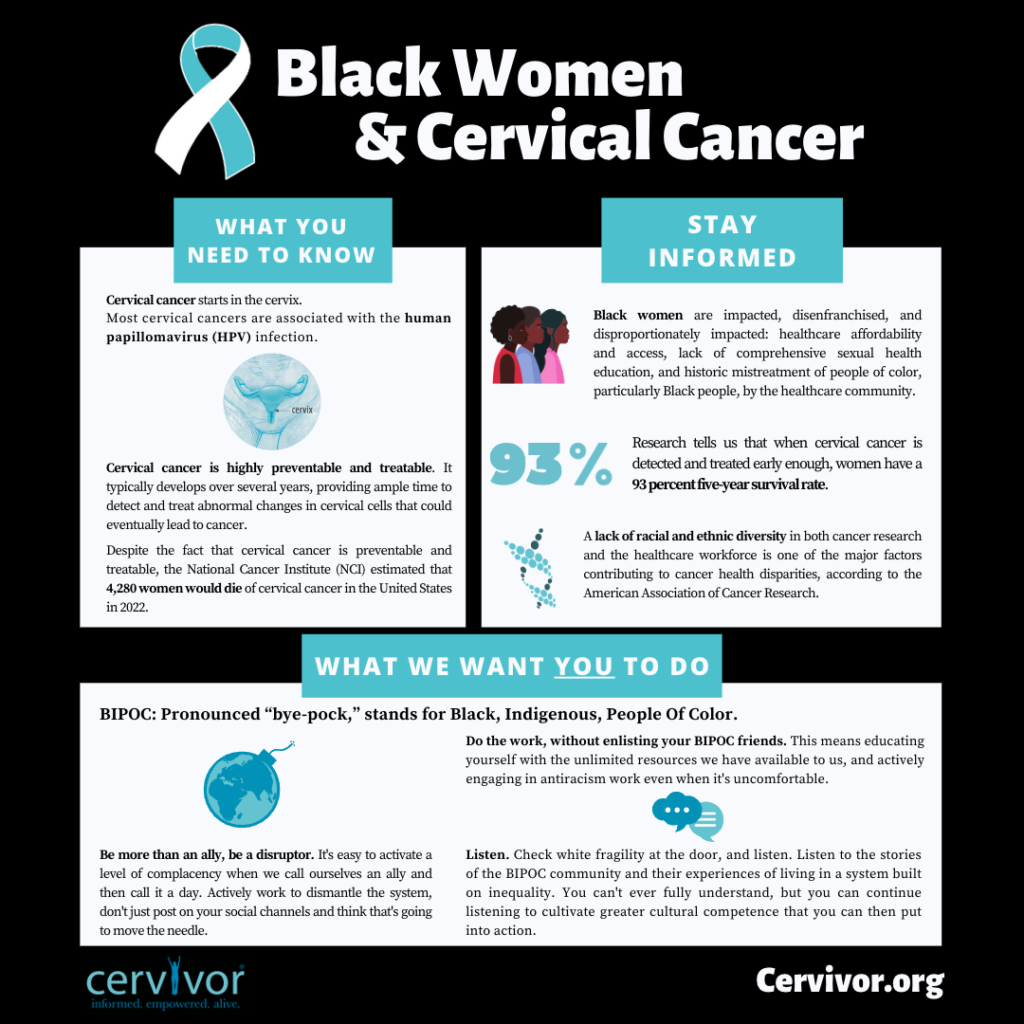

This revelation reminded me that this cause is larger than me! No one should die of cervical cancer, however, they still do. Black women are statistically more probable to die from cervical cancer and Hispanic women have the highest rate to develop cervical cancer. I’ve made it my mission to touch all diverse groups, regardless of race, creed, color, or gender to ensure they understand the importance of their gynecological health and cervical cancer screenings.

This community was built and founded by a Black woman that understands the struggles that Cervivor’s diverse community members face. There is a common theme that you may hear from any Cervivor which is “no one fights alone.” As a Black woman that has watched a community of Black women not able to address their gynecological health due to lack of insurance, child care, money, or understanding; I understand that my voice matters and holds weight within diverse populations. I intend to amplify my voice through this position to aid in decreasing the cervical cancer inequality gap that statistics show us. How you may ask? By ensuring that the Cervivor community members and any cervical cancer patient, survivor and/or thriver is supported and armed with knowledge to assist in this effort.

Connect with me on LinkedIn!

If social media is not your thing, no worries I’ve got you covered! Email me at [email protected]. I would love to connect with you as we work together to end cervical cancer. Don’t be shy, tell me how we can help close this inequality gap. You are a part of the Cervivor footprint, your thoughts, involvement, and voice matter!