By Sara Lyle-Ingersoll, Cervivor Communications Director

November is National Family Caregivers Month—a time to honor and support those tireless supporters who ensure their loved ones’ meals are prepared, appointments are kept, and hope stays alive. This year’s spotlight shines even brighter with Cancer Support Community’s CEO Sally Werner, RN, BSN, MSHA, declaring 2025 the “Year of the Caregiver.”

At Cervivor, we’re leaning into this moment with the launch of our new Cancer Caregiver Support Powered By Cervivor, Inc. Facebook group—a dedicated space for cancer caregiver connection, real talk about the hard days, and helpful resources to lighten the load.

Cervivor’s Founder and Chief Visionary Tamika Felder started the organization 20 years ago so no one affected by cervical cancer feels or fights alone—and that includes caregivers. “Caregivers need caregivers,” says Tamika, who became her father’s caregiver as a teenager before surviving cervical cancer herself. “We have to put our oxygen masks on first.”

The numbers make it clear why this focus on caregivers is so critical:

- In the U.S., about 6 million adults provide unpaid care to someone with cancer, often while also holding full-time jobs to maintain income and insurance, according to a 2023 study from the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

- On average, cancer caregivers devote 33 hours each week to care, with about one-third providing 41 hours or more—the equivalent of another full-time job, reports Healthline.

- For those supporting loved ones with cervical or gynecologic cancers, the role often includes intimate tasks like post-surgical wound care, fertility navigation, and body-image support—alongside immense emotional labor.

Ultimately, supporting caregivers means strengthening survivors, families, and the fight to end cervical cancer—Cervivor’s mission. Read on for powerful stories from our community, insights from trusted partners, and resources to help care for cancer caregivers—this National Family Caregivers Month and every month.

Why Caregivers Need Support Now More Than Ever

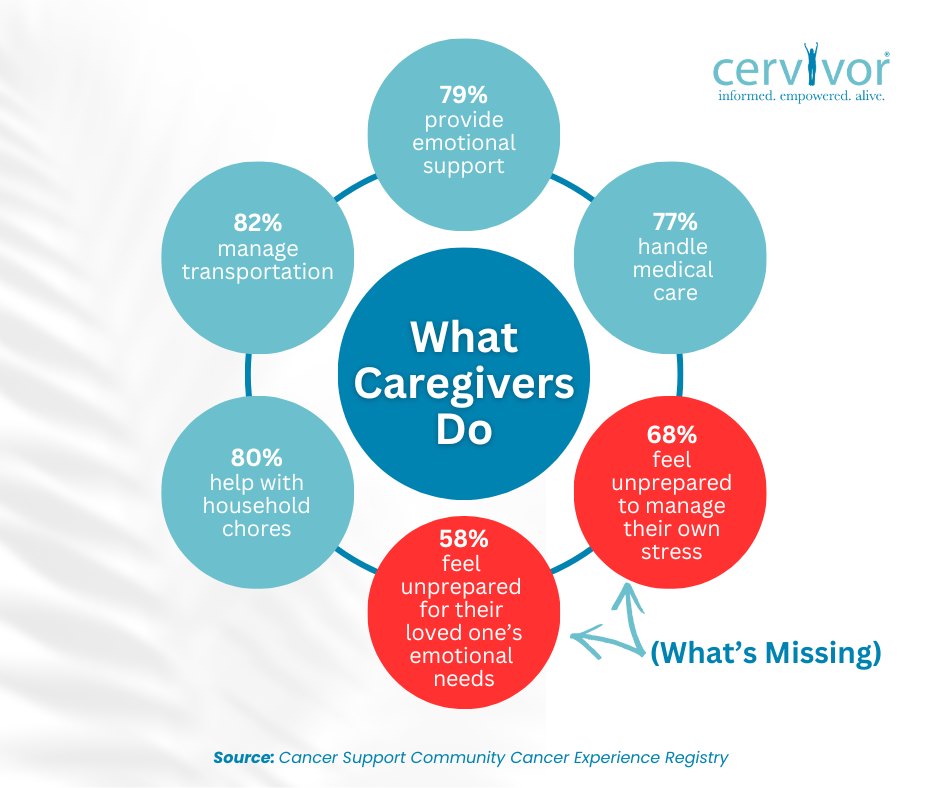

The demands of caregiving run deep, touching every corner of daily life in ways that can feel both overwhelming yet profoundly meaningful. Cancer Support Community (CSC)’s Cancer Experience Registry shows the scope of caregiving: 77% handle medical care, 79% provide emotional support, 82% manage transportation, and many juggle household chores and finances. Yet only 16% receive formal training, leaving 58% feeling unprepared for emotional needs and 68% for their own stress.

The emotional toll hits hard: Balancing work, family, and constant worry fuels burnout, guilt, and isolation. For cervical cancer caregivers, added layers like fertility loss and intimacy challenges can strain confidence and connection. “Caregiving for cervical and gynecologic cancers can be especially complex,” says Kelly Hendershot, LGSW, LMSW, Vice President of Network & Healthcare Partnerships at CSC. “Caregivers aren’t just managing logistics—they’re helping loved ones navigate emotional and physical changes that affect identity, relationships, and self-esteem.”

Financially, it’s also a strain. Recent research shows that lower-income and working caregivers face steeper challenges—lost wages, job risks, and barriers to paid leave. In 2024 alone, CSC’s helpline fielded 1,100 calls on financial stressors like bills and insurance, notes Kelly.

But there’s hope: Support systems exist—and they work. The right help at the right time can turn isolation into empowerment and exhaustion into resilience. Guides from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) andAmerican Cancer Society (ACS) highlight practical strategies like skills training for day-to-day tasks, open communication with care teams, and planned breaks to head off overload before it takes hold.

At CancerCare, Danielle Saff, Director of Social Work Programs, puts it plainly: “Our message to caregivers is simple: You are not alone, and your well-being matters.”

To bring this research to life, we’re sharing the stories of two Cervivor community caregivers: Richie Simpson, who cared for his wife, Cervivor Ambassador Arlene Simpson, and Cervivor’s Program Coordinator Lauren Lastauskas, who not only survived cervical cancer herself but also cared for her mother, Donna, through ovarian cancer until her passing in 2022. Their journeys reveal both the hardships and the resilience at the heart of caregiving.

Richie’s Story: “Laugh More than You’re Sad”

Richie’s path as a caregiver began long before Arlene’s diagnosis. He first witnessed cancer’s toll when his mother faced breast cancer in 2001. Later, he supported Arlene’s mother during her illness and cared for his own mother through pancreatic cancer until her passing in early 2018. These experiences, he says, taught him to “learn how to do old things in new ways” and to endure with love even in devastating moments.

When Arlene was diagnosed in 2021, Richie entered what he calls “the eye of the storm.” Caregiving meant everything from navigating private challenges like bladder and bowel struggles, to managing emotional highs and lows, to late-night “doomscrolling” in search of answers. His greatest fear was losing her, but humor kept them afloat: “Whatever it took to find a giggle, I’d do it.”

To avoid burnout, Richie set boundaries. He learned not to rely on empty promises of help, instead identifying true allies and specifying what kind of support was needed. As a couple, Richie and Arlene worked hard to remain partners, not just patient and caregiver. Their roles were fluid: Sometimes she cooked, other times he stepped in, cherishing the reward of her smile. After treatment, intimacy and identity required rebuilding. Richie reminded her that the woman she was post-cancer was not “less,” but stronger—and encouraged her to share her voice to inspire others.

Richie’s advice to other caregivers: Laughter is vital. Share calendars, plan ahead for high-need days, jot down questions for doctors, sit in silence when words fail, and “laugh more than you’re sad—you’re the uplifting light in their life.”

Lauren’s Story: A Legacy That Keeps Giving

Lauren’s caregiving story spans generations. At 23, she was diagnosed with cervical cancer, with her mother Donna by her side for every appointment, surgery, and recovery milestone. Donna had long been the family’s caregiver—caring for her own mother through breast cancer recurrences and her sister through late-stage lung cancer.

Years later, Lauren found herself caregiving in turn: First for her sister-in-law during breast cancer treatment in 2019, and then for her mother, who was diagnosed with stage 4 ovarian cancer in late 2021. By Christmas that year, doctors gave her a prognosis of six to eight months.

Lauren became Donna’s healthcare power of attorney, managing treatments, coordinating hospice, and making painful decisions. She helped bathe her, administered medications, and even accompanied her to the funeral home to ensure her wishes were honored. Donna passed away at home on May 7, 2022, surrounded by family.

For Lauren, caregiving brought exhaustion, isolation, and moments of resentment—but also profound love. “Even after, I’m still her caregiver—just grieving, honoring her,” she shares.

Cervivor’s founder Tamika remembers Donna as one of the organization’s earliest champions: “She was passionate, opinionated, and determined to make things happen for this community. She fundraised in gymnasiums, made signs, and wasn’t afraid to tell me exactly what Cervivor needed. I think she would be so proud to see Lauren carrying the torch now.”

Today, Lauren sees caregiving as an extension of survivorship: “Strength isn’t pretending; it’s choosing love. You’re doing your best; that’s enough. Love is a daily choice.”

How to Care for Caregivers—Starting Today

The research is clear, and so are the lived experiences of cancer caregivers of Richie and Lauren: This work takes an enormous toll. Many feel underprepared and undersupported. What they need most is not only recognition, but also practical, accessible tools to help them sustain both their loved ones and themselves.

Whether you’re caregiving, surviving, or supporting from afar, these trusted resources can help:

- Cancer Support Community (CSC) offers free support groups, workshops, and the MyLifeLine app, which includes a Helping Calendar to simplify requests for rides, meals, childcare, pet care, and more. The app also provides a message forum for cancer caregivers and the option to create a private website to document your journey. CSC’s nationwide Helpline (888-793-9355) is always available. “Support groups were my lifeline,” says Kelly from CSC, who was a caregiver herself. She also reminds fellow caregivers: “Rest isn’t selfish—it’s necessary.”

- CancerCare provides free virtual and in-person counseling, workshops, toolkits, publications, and My Cancer Circle, an online platform that helps families and friends coordinate care. Its HOPEline (800-813-HOPE) is available Monday to Thursday from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. EST and Friday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. EST. “Caregiving is an act of love, but it can also be exhausting, overwhelming, and isolating,” says CancerCare’s Danielle. “When you care for yourself, you’re better able to care for your loved one.”

- American Cancer Society (ACS) offers practical tools for cancer caregivers like the Caregiver Resource Guide. Their 24-7 Helpline is 1-800-227-2345.

- National Cancer Institute (NCI) has a Support for Caregivers page and a downloadable Caring for the Caregiver booklet. NCI emphasizes practical skills for communication, stress management, and daily caregiving.

- Family Caregiver Alliance and the Administration for Community Living (ACL)’s National Family Caregiver Support Program provide respite programs, caregiver training, and navigation for financial assistance.

Tamika emphasizes why National Family Caregivers Month truly matters: “When we support caregivers, we strengthen survivors, families, and outcomes. Behind every Cervivor is someone who shows up with love and strength.”

Richie adds that finding a community is essential: “Connecting makes all the difference. You realize you’re part of something bigger.”

Interested in joining Cervivor’s new cancer caregivers Facebook group? Fill out this form to connect with peers, share your story, and find resources that lighten the load.

About the Author

SARA LYLE-INGERSOLL is a seasoned content and communications expert dedicated to transforming lived experiences into impactful stories. Her award-winning magazine feature about a close friend who passed from cervical cancer in their twenties led her to connect with Cervivor’s founder, Tamika Felder, and solidified her commitment to cervical cancer awareness and prevention. Now, as Cervivor’s Communications Director, Sara brings this mission full circle.