By Kyle Minnis, Cervivor Communications Assistant

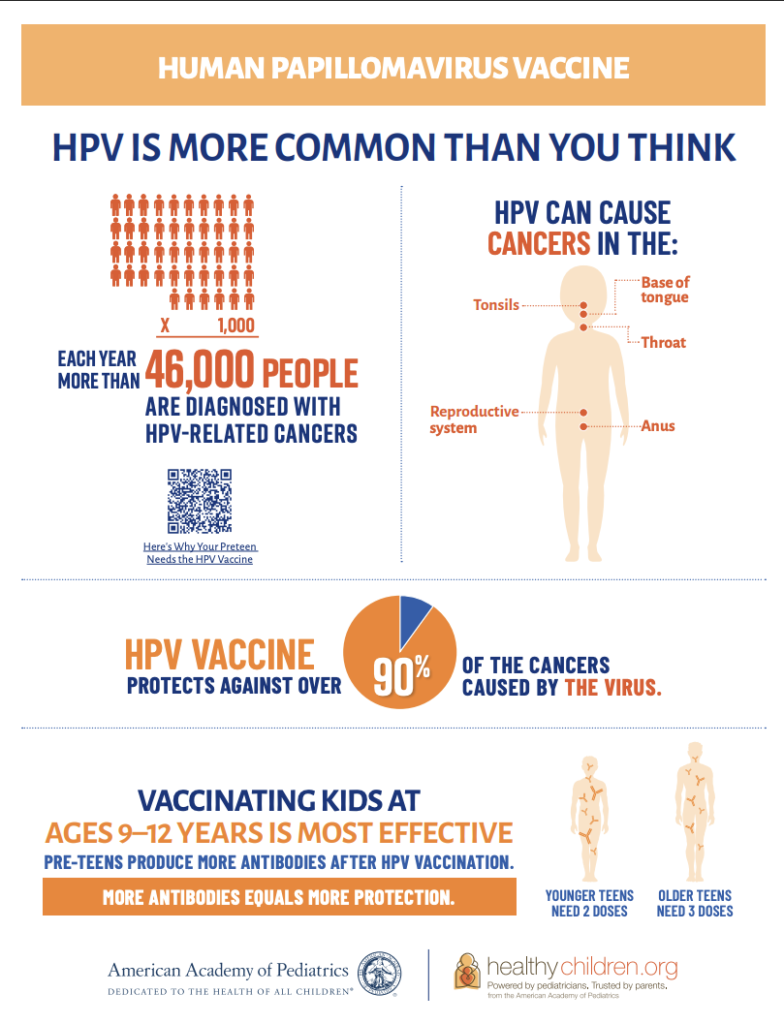

The United States, along with much of the world, is at a pivotal moment in cancer prevention. Various studies show that use of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine—which can prevent over 90% of HPV-related cancers, including cervical cancer—is falling. If the trend continues, more children and families will face potentially life-threatening cancer diagnoses that could be avoided.

The numbers speak for themselves: According to the Centers for Disease Control’s (CDC) most recent National Immunization Survey, only 78% of U.S. adolescents aged 13 to 17 have received at least one dose of the HPV vaccine, and fewer than 63% are up to date on the full series. This is significantly below the national Healthy People 2030 goal of 80% two-dose completion among adolescents aged 13 to 15. Recent data suggests the pandemic has widened gaps in vaccine uptake and fueled vaccine hesitancy.

Globally, approximately 31% of eligible girls have received at least one dose, though the percentage fully completing the recommended series falls well short of the World Health Organization (WHO) cervical cancer elimination target of 90% completion by age 15. The disease still claims the lives of nearly 400,000 people with a cervix worldwide each year.

As vaccine misinformation floods social media, parents and young adults encounter more conflicting messages than ever. Meanwhile, research infrastructure is under threat. In March 2025, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) terminated all funded research on vaccine hesitancy and uptake, telling scientists: “This award no longer effectuates agency priorities.”

“Watching the headlines and talking to experts in the field, we know this is a critical time,” says cervical cancer survivor Tamika Felder, Cervivor’s Founder and Chief Visionary and co-chair of the American Cancer Society’s National HPV Vaccination Roundtable. “Respected scientists are being dismissed. Research is being defunded. ‘Vaccine’ has become an even more loaded word. And decades of hard-earned progress are at risk.”

For Cervivor Ambassador Zuli Garcia, who will mark her second cancer-versary this November, the issue is deeply personal. As a 2024 Cervivor School graduate and founder of Knock and Drop Iowa, she advocates for underserved families who often face barriers to timely HPV cancer prevention. “I’m living proof of what happens when access comes too late,” says Zuli, who was diagnosed at age 47. “The HPV vaccine represents hope, protection, and equity.”

To cut through the noise and offer clear, trustworthy HPV vaccine facts during National Immunization Awareness Month (NIAM), we’ve gathered insights from survivors and leading experts. What follows is a breakdown of the most essential information about the HPV vaccine—and why it’s needed to protect future generations from preventable cancers.

Why HPV Vaccination Matters More Than Ever

Every major health authority agrees: The HPV vaccine saves lives from cervical cancer and five other HPV-related cancers—including anal, throat, penile, vaginal, and vulvar cancers. Among teen girls, infections with the HPV types that cause most cancers have dropped by 88%, while infections among young women have dropped by 81%, according to a 2024 CDC report. Additionally, among vaccinated women, cervical precancers caused by high-risk HPV types have declined by 40%, with some studies showing up to 80% reductions in high-grade lesions among those vaccinated early.

In countries like Australia and Sweden—thanks to widespread vaccination and strong screening programs—HPV is close to being eliminated as a cause of cervical cancer.

Dr. Heather Brandt, director of the HPV Cancer Prevention Program at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, stresses both the progress made and the work still ahead. “Here we are after almost 20 years of the vaccination being available and still working to make sure people understand how HPV vaccination protects against these diseases,” she says. She recalls feeling “such excitement” at the 2002 International Papillomavirus Conference when early trial results showed the vaccine could prevent HPV-related diseases, pre-cancers, cancers, genital warts, and even recurrent respiratory papillomatosis.

Today, after more than 15 years and over 500 million doses given worldwide, the vaccine’s safety record remains excellent. Serious side effects are extremely rare, and most reactions are mild, such as temporary soreness or fever. Real-world studies confirm that protection lasts at least 12 years—and likely much longer.

Who Should Get the HPV Vaccine and When?

Everyone—regardless of gender—should get the HPV vaccine. Here are the latest immunization guidelines:

- The ideal time to start is between ages 11 and 12, though it can be given as early as age 9 for maximum protection.

- If the first dose is given before age 15, only two doses are needed.

- For those starting later or who are immunocompromised, a three-dose series is recommended.

- Catch-up vaccination is advised through age 26, and adults up to age 45 may still benefit based on individual risk and guidance from their healthcare provider.

The following infographic provides additional information on when and why the vaccine is so important for saving lives from preventable cancers.

While insurance coverage for older teens and adults varies, several states—including Washington D.C., Virginia, Rhode Island, and Hawaii, plus Puerto Rico—have implemented school-entry requirements for the HPV vaccine. These policies significantly boost community-wide protection.

“HPV affects everyone—men and women—and the vaccine is about cancer prevention, not lifestyle choices,” says a spokesperson from Vaccinate Your Family, an organization dedicated to raising awareness about timely immunizations. Its current #FirstDayVax campaign aligns with CDC recommendations to bundle the HPV vaccine with other routine back-to-school shots, like Tdap and meningitis.

Common HPV Vaccine Myths—and How to Address Them

Across the U.S.—especially in rural and conservative communities—misinformation and stigma are stalling progress. Rising non-medical exemptions, often fueled by online disinformation, threaten decades of gains for all vaccines, not just HPV. Without research and infrastructure support, public health programs are left without the tools they need to respond.

As Vaccinate Your Family warns: “Parents are increasingly exposed to false vaccine claims online, where algorithms and bots amplify misleading content and make anti-vaccine rhetoric appear as credible as scientific consensus.”

Even parents who support vaccines can be swayed. Kellie Defelice, a Cervivor Ambassador, shares: “I was very pro-vaccine. But after reading a story online, I hesitated and turned down the HPV vaccine for my daughter. I regretted that decision when I was diagnosed with cervical cancer.” Her hope for fellow moms: “They see that I’m the real face of what HPV does—it isn’t just an STI. I risked my daughter getting a cancer that has destroyed so much for me.”

Other common myths include:

- “The HPV vaccine is just for girls.” In fact, HPV affects everyone. Anal cancer rates in both men and women have been rising, with new cases increasing by about 2.2% per year over the past decade, according to the American Cancer Society. While men may not get cervical cancer, they can still contract and spread high-risk HPV strains.

- “The vaccine encourages promiscuity.” Zuli explains that some parents worry the vaccine is a “permission slip for sex.” But as Vaccinate Your Family counters, “Vaccination does not change behavior—it simply protects against cancer-causing infections.”

- “The vaccine isn’t necessary until kids are sexually active.” In reality, the vaccine works best before HPV exposure, which is why health organizations now recommend it for children as young as 9 years old.

How to Get Back on Track with HPV Vaccination Targets

Survivors and experts are pushing back against misinformation with evidence, stories, and culturally relevant outreach. Zuli says: “As a survivor, I’ll keep raising my voice until every child, every family, and every community has access to this protection.”

A review of nearly 60 studies conducted between 2006 and 2019 found that strong provider recommendations are among the most important—if not the most important—drivers of vaccine uptake, underscoring the need to equip health professionals with confidence and clarity in vaccine conversations.

Community partnerships also make a difference. In Memphis, the St. Jude HPV Cancer Prevention Program helped boost county vaccination rates by 19%, outpacing national averages. In Iowa, Zuli’s team at Knock and Drop Iowa combines bilingual education with on-site vaccinations—reaching 23 people in a single afternoon, she reports. “Meeting people where they are is what works,” Zuli explains. “Education first, vaccines immediately after, in a trusted setting.”

Vaccinate Your Family echoes this approach: “Conversations about vaccines should always start with empathy, not judgment. Questions about safety, side effects, or the need for certain vaccines are natural—and families should look to trusted, science-based sources.”

St. Jude’s Dr. Brandt highlights new “compelling” research: “Through our work…we have been discussing the implications of possible changes to the dosing schedule with partners. I know all of us are incredibly excited about the prospect of moving to a single dose in the U.S.”

She also offers caution: “We previously leaned in on the rigor of the FDA-approval processes for childhood vaccinations and then review by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Key changes to these entities may call into question the science. Changes in dosing with any gaps in evidence become fodder for purveyors of misinformation.”

Ultimately, cancer prevention shouldn’t be controversial—it should be celebrated. By recommitting to science, survivor voices, and trusted outreach, we can ensure every person has the chance to thrive, free from preventable cancers.

If you found this blog post helpful, please share it with friends or family members of recommended vaccination age. You may just save a life.

About the Author

Kyle Minnis is a senior studying Strategic Communications at the University of Kansas. He is currently serving as Cervivor’s Communications Assistant.