Is it really possible to eliminate cervical cancer—not just reduce it or manage it, but wipe it off the map for good? The World Health Organization (WHO) says yes, and has set ambitious global targets to get there by 2030.

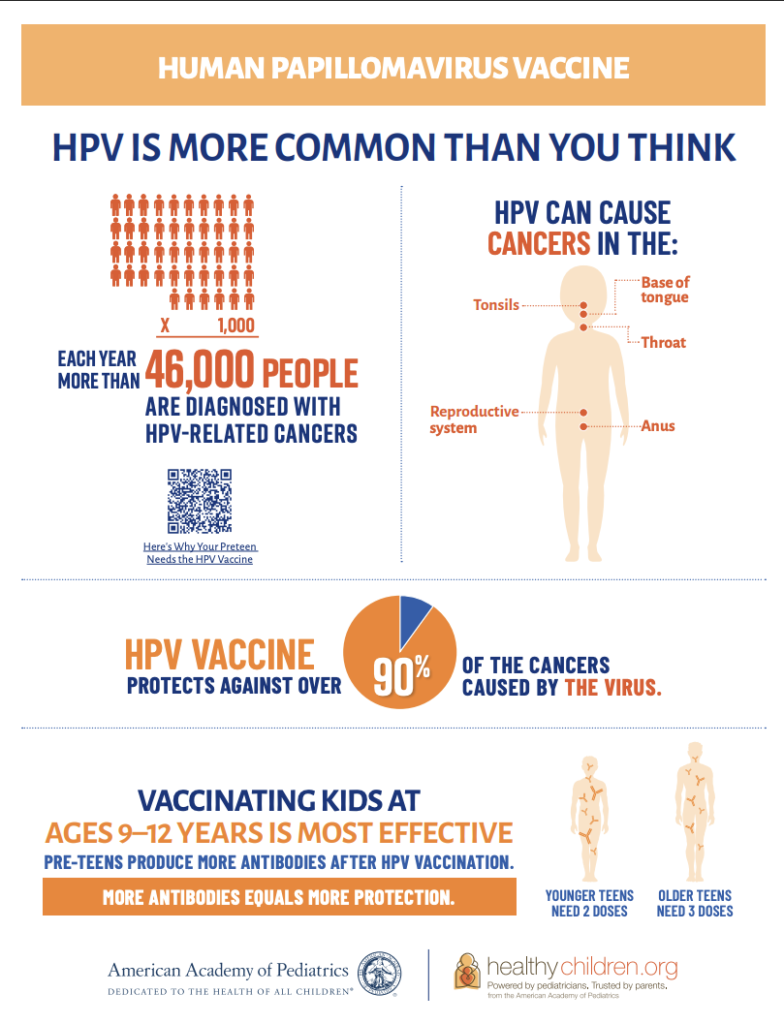

The WHO’s 90‑70‑90 cervical cancer elimination strategy calls for:

- 90% of girls vaccinated against HPV by age 15

- 70% of women screened by age 35 and again at 45

- 90% of those diagnosed receiving timely treatment

But meeting this deadline will take more than aspiration—it will take collective action. And today is a major step forward.

November 17, 2025, is the first-ever World Cervical Cancer Elimination Day, designated earlier this year by the World Health Assembly. Think of it like World AIDS Day or World Polio Day—global observances that didn’t just raise awareness, but helped spark the vaccines, screenings, and policies that pushed those diseases to the brink of eradication.

Cervivor, Inc. Founder and Chief Visionary Tamika Felder and Nigeria’s First Lady and healthcare pioneer, Dr. Zainab Shinkafi-Bagudu, were among the leaders who advocated for the day’s creation, including co-authoring a global call to action via the World Economic Forum to support it and elevate its importance on the world stage.

“I started Cervivor 20 years ago to support those affected by cervical cancer, hoping one day it wouldn’t be needed,” Tamika reflected at the time. “But too many communities are still suffering and dying from this preventable disease. A global day of recognition sends a powerful message: Awareness isn’t enough—the time for education, action, and elimination is now.”

Below, we bring you an exclusive Q&A with Tamika and Dr. Bagudu, who is also Founder and CEO of the Medicaid Cancer Foundation and President-elect of the Union for International Cancer Control (UICC), answering the same questions from Maryland, USA, and Kebbi State, Nigeria, respectively. Their voices—one from the frontlines of African health equity and the other from the heart of patient advocacy—remind us: Elimination isn’t a solo act. It’s a chorus.

Q: Why does World Cervical Cancer Elimination Day matter?

Tamika: As a cervical cancer survivor, this day feels deeply personal. It represents something I once couldn’t imagine: hope for a world where no one else has to hear the words “you have cervical cancer.” When the World Health Organization declared that eliminating cervical cancer is within reach, it turned our fight from awareness into action.

For survivors, this first official World Cervical Cancer Elimination Day is a milestone that honors every story, every loss, and every victory along the way. It reminds us that our voices matter and that lived experience can guide smarter policies, stronger outreach, and more compassionate care.

Dr. Bagudu: World Cervical Cancer Elimination Day is symbolic—a rallying point for action. The WHO’s declaration that elimination is within reach shows this is an achievable reality if we commit to the right strategies.

- Globally, it unites countries around a common goal: HPV vaccination, wider screening, and timely treatment. As President-elect of the UICC, I see this observance as a vital tool to keep cervical cancer high on the agenda, especially for low- and middle-income countries.

- Nationally in Nigeria, it validates years of advocacy by First Ladies Against Cancer (FLAC), which I co-founded. The FLAC Screening Clinic in Kebbi is one example of how global commitments can translate into local action.

- Personally, it is deeply meaningful. As a physician, mother, and advocate, I have seen both the devastation of late diagnosis and the hope that comes with early screening or HPV vaccination.

Ultimately, this day transforms aspiration into accountability. It tells the world: We can, and we must, eliminate this disease in our lifetime.

Q: How can a global day like this drive real change?

Tamika: We’ve seen the power of global observances before. Days like World AIDS Day and World Polio Day didn’t just raise awareness; they mobilized action, funding, and accountability. World Cervical Cancer Elimination Day can do the same.

In the United States, it can shine a light on the inequities that persist in prevention and care while inspiring innovation and collaboration. When survivors, clinicians, policymakers, and advocates unite around a shared message, we can accelerate progress toward eliminating this preventable cancer.

Dr. Bagudu: Nigeria has made important strides. The government’s rollout of the HPV vaccination program is a landmark step, protecting millions of young girls. Screening services are also expanding, with initiatives like the FLAC Screening Clinic in Kebbi showing how early detection can be brought closer to communities.

Civil society has been central. Through First Ladies Against Cancer (FLAC), we’ve sustained awareness campaigns, mobilized resources, and ensured continuity of programs. Partnerships with groups like Roche and the Clinton Health Access Initiative have strengthened diagnostics and treatment pathways. And of course, the Medicaid Cancer Foundation is at the heart of it all.

Still, challenges remain. Many rural women face barriers of distance, cost, and stigma. Shortages of trained health workers delay follow-up and treatment. And while HPV vaccines are now part of the national program, consistent supply and uptake across all states will require sustained political will and funding.

For me, this progress proves that change is possible when government, civil society, and partners work together. But it also reminds us that elimination will not happen automatically—it demands accountability, innovation, and persistence.

Q: Why is cervical cancer elimination especially urgent in low-resource regions?

Tamika: The U.S. has the knowledge and tools to prevent nearly all cervical cancers, yet persistent inequities mean prevention isn’t reaching everyone. Communities of color, people in rural areas, immigrants, people without reliable insurance, and those with language or transportation barriers face higher risks and lower access to vaccination, screening, and timely treatment. As a survivor, I know how much access, awareness, and advocacy can determine outcomes.

Elimination in the U.S. must start with equity. That means expanding vaccination access in schools and clinics, funding community-led education, and supporting policies that make screening and treatment affordable and available for everyone. Until every community is reached, we have not truly achieved elimination.

Dr. Bagudu: Cervical cancer is a stark example of global health inequity. While it is increasingly rare in high-income countries, including the U.S., it remains a leading cause of cancer deaths in Africa, where women are more likely to be diagnosed late, less likely to access treatment, and more likely to die from a preventable disease.

In Nigeria, the challenges are clear:

- Access is uneven; urban women may find screening in tertiary hospitals, but rural women face long distances, high costs, and limited awareness.

- Stigma and cultural barriers discourage care until symptoms are advanced.

- Health system gaps include shortages of trained personnel, diagnostic tools, and reliable vaccine supply chains.

Yet there are real opportunities. The national HPV vaccination rollout can protect millions of girls. Screening is expanding through models like the FLAC Clinic in Kebbi, which shows how state leadership can drive change. Through the Medicaid Cancer Foundation and First Ladies Against Cancer, we’ve raised awareness, supported patients, and built partnerships that strengthen care.

As President-elect of UICC, I can amplify Africa’s voice globally, while at the grassroots, we continue training health workers and engaging communities. Cervical cancer elimination is urgent because every delay costs lives—but with political will, investment, and collaboration, it is achievable, and African women must not be left behind.

Q: What progress have you seen—and what gaps remain?

Dr. Bagudu: We are at a turning point. In Nigeria and across Africa, real progress has been made against cervical cancer.

The national HPV vaccination rollout is a landmark milestone, protecting millions of girls. Screening services are expanding, with clinics like the FLAC Screening Clinic in Kebbi, and awareness campaigns are beginning to shift cultural attitudes. Treatment capacity is also improving, with more cancer centers equipped for radiotherapy and chemotherapy, while education efforts keep cancer high on the agenda.

Still, the gaps are stark. Too many women are diagnosed late, rural and low-income communities face barriers of distance, cost, and stigma, and health systems struggle with workforce shortages, supply chain issues, and limited palliative care.

This is why innovation is critical. Self-collection for HPV testing, digital health tools, mobile outreach, and task-shifting to community health workers can expand access dramatically.

The Medicaid Cancer Foundation (MCF) is helping bridge these gaps by running awareness campaigns, supporting screening in urban and rural areas, providing financial and psychosocial support through our PACE program, and advocating for sustainable funding and best practices. Beyond Nigeria, we collaborate with regional and global partners to strengthen advocacy and ensure Africa’s challenges are reflected in international strategies.

In short, progress is real, but urgency remains. With innovation, collaboration, and sustained commitment, we can close the gaps and move decisively toward eliminating cervical cancer across the continent.

Tamika: From where I stand, what’s changing most is momentum. More people are learning that HPV causes cervical cancer, vaccination rates are improving in some regions, and new technologies like HPV self-collection are showing incredible promise. Survivors are stepping into leadership roles and helping shape the national conversation about prevention and equity.

But there is still work to do. Too many people remain unaware of their risk or lack access to timely screening and treatment. Stigma and fear continue to silence conversations about cervical health. Organizations like Cervivor are helping bridge those gaps by elevating survivor voices, promoting education, and partnering with health systems to ensure innovations reach those who need them most.

Q: What message would you share on this inaugural day?

Tamika: A future without HPV-related cancers looks like prevention in every community, equity in every policy, and hope in every story. It looks like the next generation growing up protected and informed. A world without cervical cancer means no more stories like mine—and that’s the legacy I want to leave behind.

Elimination is possible, but it will take continued investment, accountability, and survivor leadership. Those of us who have lived through cervical cancer know what’s at stake, and we’re committed to making sure no one else has to.

Dr. Bagudu: On this inaugural World Cervical Cancer Elimination Day, my message is one of hope and urgency. Hope—because for the first time, we have the tools to end a cancer. Urgency—because every year of delay costs thousands of women’s lives, especially in Africa.

A future without HPV-related cancers is one where girls are routinely vaccinated, women have access to simple, affordable screening close to home, and treatment is available without stigma or financial hardship. It is a future where communities celebrate survivorship rather than mourn preventable loss.

To get there, governments must prioritize vaccination, screening, and treatment; global partners must ensure equitable access; and civil society—including the Medicaid Cancer Foundation—must continue raising awareness, supporting patients, and holding leaders accountable. Innovation, from self-collection for HPV testing to digital health tools, will also be key.

If you found this blog post helpful, please share it with friends and family. Knowledge is power—and you may just save a life. Questions? Contact us at [email protected].