By Kyle Minnis, Cervivor Communications Intern

Today, an estimated one million LGBTQIA+ cancer survivors live in the United States—a fraction of the nation’s nearly 19 million survivors. But behind that number lies an alarming reality: Queer and trans individuals face higher rates of late-stage diagnoses, limited access to screening, lower insurance coverage, and deep-rooted mistrust in the medical system. Experts warn these disparities may worsen before they improve.

At Cervivor, Inc., we believe every cervix matters. This Pride Month, we’re shining a light on the barriers queer and trans individuals face in accessing cervical cancer care—and how we can work together to break them down. (Missed part one of the series? Read the powerful stories of four courageous Cervivor Pride community members.)

Mounting Setbacks in LGBTQIA+ Cancer Care Access

Over the past year, federal datasets on sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) have quietly been removed from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) websites, setting back critical research and advocacy efforts. Carter Steger, Vice President at the American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network (ACS CAN), calls the change “unclear and alarming.”

The setbacks go beyond data. Dr. Mandi Pratt-Chapman, a leading LGBTQIA+ health researcher at the George Washington University Cancer Center, reports that all National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded LGBTQIA+ research grants—including her own—have been terminated. “We can’t just flip the switch back on,” she warns. “The infrastructure has already been dismantled.”

At the same time, state-level legislation is emboldening discrimination in healthcare. The recent U.S. Supreme Court ruling in United States v. Skrmetti upheld states’ rights to deny gender-affirming care to minors, raising broader concerns about refusals of service.

“Before this immense backlash on LGBTQIA+ civil rights, we were finally making progress,” says Dr. Pratt-Chapman. “As a society, we collectively said—you are part of our community! Now, that message of inclusion and protection—indeed, actual protection—is being torn away in a deliberately hurtful and terrifying way.”

Safe Spaces Are Shrinking—and Medical Mistrust Is Growing

According to ACS CAN’s latest Survivor Views survey, 58% of LGBTQ+ cancer patients fear the current political climate could directly impact their access to care. Nearly half worry that providers may consider it “too risky” to treat them due to state laws.

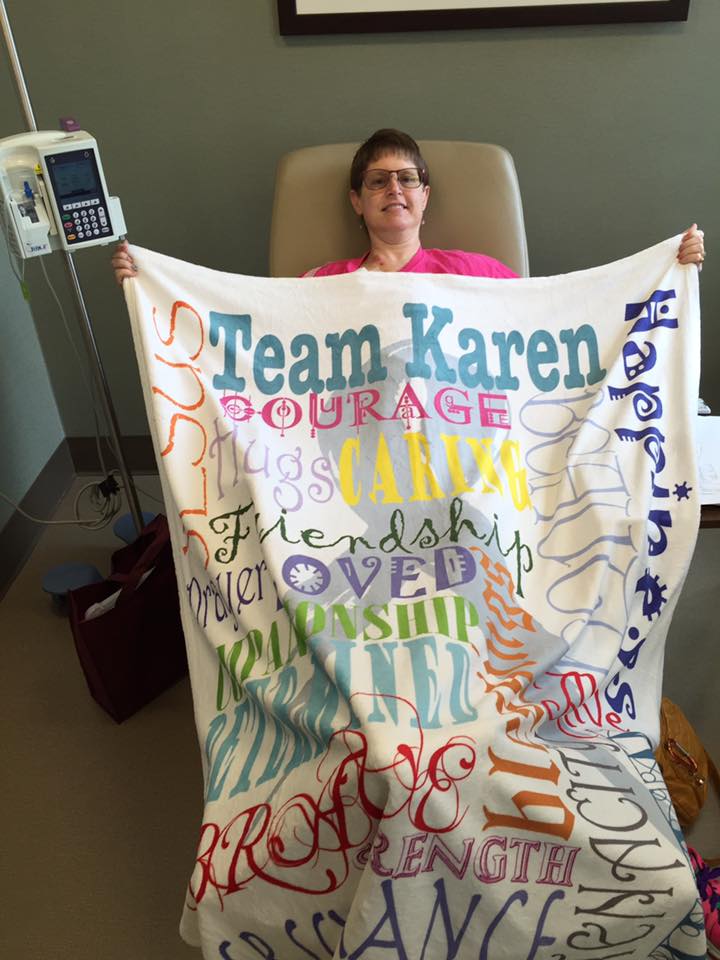

Cervivor Pride lead Karen North puts it bluntly: “I’m scared. They’re coming for people like me—my identity, my rights.”

Cervivor Ambassador Gilma Pereda, whose adult daughter is a trans woman, shares similar fears: “Being a transgender young woman and neurodivergent is a very bad combo in today’s political climate. I’m terrified. We have a plan B—moving to Mexico City, where I’m from, for universal healthcare. She’s not on board yet, but it’s our last resort.”

This anxiety is becoming more common. “People are trying to move to blue states or Europe,” says Dr. Scout, Executive Director of the National LGBT Cancer Network. “We’re watching our safe spaces and experts disappear before our eyes.”

Even in well-meaning systems, barriers persist. Intake forms often lack inclusive options for sexual orientation and gender identity. Most medical students receive fewer than five hours of LGBTQIA+ health education in their entire training. And in response to political pressure, some hospitals have quietly removed LGBTQIA+-affirming content from their websites to avoid backlash or funding threats.

The result? Deepening medical mistrust. “For too many of us, the core issue is not knowing whether a provider will treat us with dignity,” says Dr. Scout. “The simple fix is for more providers to make that clear—somewhere visible—so we can get past the mistrust and through the door.”

This fear often leads to skipped care. Lesbians without trusted OB-GYNs are less likely to get screenings like Pap tests or mammograms. Transgender men may avoid gynecologic care entirely.

But small signals of safety can make a big difference. A name tag with pronouns. A “You’re Safe With Me” sign. According to Dr. Scout, LGBTQIA+ patients are nearly seven times more likely to rate their care as “very good” when they see visible signs that their identity will be respected.

Gilma highlights “small but meaningful changes” she’s seen at her healthcare provider in progressive California. “The clinic I go to used to be called the ‘Women’s Clinic,’ but now it says ‘Gynecology and Obstetrics,’” she says. (The word “women” can be triggering for many trans men and LGBTQIA+ patients.) “I also remember a sign at reception that said something like, ‘If you don’t feel comfortable waiting in this room, please let us know and we’ll move you.’ I wish I had taken a picture—it really stood out to me.”

The Financial Cost of Care

For many queer and trans people, even seeking healthcare comes with roadblocks—starting with insurance. According to the Cancer Network, LGBTQ+ individuals are less likely to have health coverage, often because employers don’t extend benefits to unmarried domestic partners. This gap is even wider for transgender individuals, who have the lowest insurance coverage rates of any group.

Even with insurance, coverage is not guaranteed. Transgender patients may be denied access to gender-relevant care—such as Pap tests for trans men with a cervix—if it doesn’t match the gender on their insurance card. These mismatches can delay or deny vital screenings.

Gilma knows just how rare affirming, comprehensive care can be. “We’re very privileged to have Kaiser [in the Bay Area],” she says, noting how her daughter was able to update her name and gender in the system and receive respectful care. “That’s not the case everywhere.”

Women in same-sex relationships face similar challenges. They’re less likely to have a regular healthcare provider, often citing cost as a barrier—leading to lower screening rates for mammograms, Pap tests, and colonoscopies, which raises the risk of late-stage diagnoses.

Government safety nets like Medicaid help fill these gaps, but even they’re under threat. “When I got cervical cancer, I was on Medicaid,” says Karen. “That’s what allowed me to get treatment. If Medicaid cuts continue—if the Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program goes away—that’s terrifying. That program saved my life.”

Karen is referring to the 30-year-old public health initiative that has provided life-saving screenings to women with low incomes and limited insurance. Now, that vital lifeline is at risk. Dr. Pratt-Chapman echoes the concern, warning that proposed cuts could also eliminate federal cancer registries—undermining efforts to prevent cancer and catch it early.

Despite these threats, a legal win offers a glimmer of hope. In the recent APHA v. NIH case, U.S. District Judge William G. Young of Massachusetts deemed the Trump administration’s termination of hundreds of NIH research grants “arbitrary and capricious,” and therefore “void and illegal.” He stated these cuts “represent racial discrimination and discrimination against America’s LGBTQ community,” ordering the restoration of nearly $3.8 billion across 367 affected projects for the time being.

Building a New Kind of Safety Net

Even as the landscape grows more fractured and unpredictable, people are still planting new flags—big, bold, rainbow ones.

Organizations like ACS CAN and the Cancer Network are strongly advocating for inclusive legislation. This includes the Health Equity and Accountability Act (HEAA), which would require the collection of data on sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) in federal health surveys, and the Equality Act, which would explicitly ban discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity, and sex characteristics across all sectors, including healthcare.

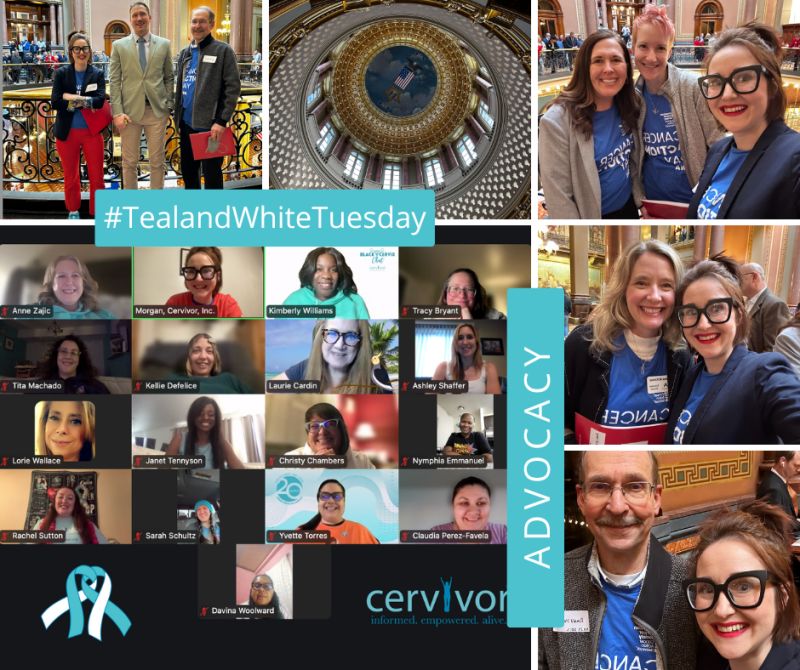

These policy fights are being matched by boots-on-the-ground action. ACS CAN’s LGBTQIA+ & Allies Engagement Group supports strategy development, educates advocates, and ensures queer visibility in campaigns and Pride events. In 2025, the organization will appear at more than 60 Pride events across 32 states.

The group also recently hosted a virtual screening of Trans Dudes with Lady Cancer, a powerful documentary following two transmasculine individuals navigating breast and ovarian cancer care, sparking dialogue about gender, inclusion, and systemic change.

Training efforts are also expanding. GW Cancer Center’s TEAM training offers free, online education for healthcare providers looking to improve LGBTQIA+ cancer care, and a new version, TEAM SGM, aims to provide a deeper dive for oncology-specific scenarios. The Cancer Network also provides Welcoming Spaces training, helping providers build physical and emotional environments where patients feel respected, affirmed, and safe.

Take Action: Stand With the LGBTQIA+ Cancer Community

This is a critical moment. Cancer doesn’t discriminate, and neither should the systems designed to help us survive it.

The challenges are real, but they are not insurmountable—and they are not going unnoticed.

“I want to be in that group of people,” says Dr. Pratt-Chapman. “The ones history celebrates for standing up when it got hard. Hate shrinks the world. Love is expansive. Love brings life.”

What can you do?

- Contact your elected officials today to protect and expand funding for cancer research, Medicaid, and programs like the Early Detection Program. Take action at act.fightcancer.org.

- Encourage local clinics and hospitals to provide LGBTQIA+ cultural competency training. Providers can join programs like TEAM or Welcoming Spaces.

- If you’re a patient or survivor, share your story—you never know who needs to hear it.