In this second blog post for AANHPI Heritage Month, we explore the health disparities affecting Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander cervical cancer survivors.

Previously, Cervivor community members Arlene Simpson (Filipina), Joslyn Chaiprasert-Paguio (Chinese-Thai), Anna Ogo (Japanese), and Anh Le (Vietnamese) shared their diverse experiences, revealing a shared truth: While stigma and cultural silence around cervical and other “below-the-belt” cancers are common, their impact varies across AANHPI communities.

Despite these differences, many face similar systemic barriers to prevention, screening, and timely care—barriers that continue to cost lives. Case in point:

- According to the American Cancer Society, Pap test screening is significantly lower among Chinese (69%) and Asian Indian (74%) women compared to white women (84%). This gap in screening may contribute to later-stage diagnoses and worse outcomes.

- HPV vaccination rates also lag behind national averages. A 2023 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) report found that only 58% of Asian American adolescents had initiated the HPV vaccine series—lower than their Hispanic (73%) and White (61%) counterparts.

- A 2024 ACS article also noted that while cervical cancer rates are higher in some parts of Asia, many AANHPI individuals are unaware of risks based on their country of origin.

Experts and survivors highlight the following key challenges to reversing these trends as well as some promising progress:

Language Barriers

Asian Americans come from over 30 countries and speak more than 100 languages and dialects, explains Dr. Ha Ngan “Milkie” Vu, Assistant Professor at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine. These linguistic and cultural differences often make accessing health information difficult.

As Arlene shares, “Medical terms don’t always translate clearly, and jargon makes it harder. Even basic words like ‘cervix’ don’t translate well in some cultures.” Joslyn, featured in Everyday Health, says, “In Thai, there’s no direct word for cervix—it’s described as a ‘plug’ that keeps the baby in. Without a proper term, how do you talk about your body?”

These communication challenges are often compounded by a lack of in-language medical materials. Dr. Jennifer Tsui, Associate Professor of Population and Public Health Sciences at USC’s Keck School of Medicine, recalls translating for her Asian immigrant grandparents at medical visits—an experience common to many second-generation individuals. Through her current work on the National Cancer Institute-funded ACHIEVE Study, which examines barriers to cervical cancer treatment and survivorship care, she has found that many patients want materials in their native language to understand whether the vaccine has been tested in their communities and if it’s effective for different Asian American groups.

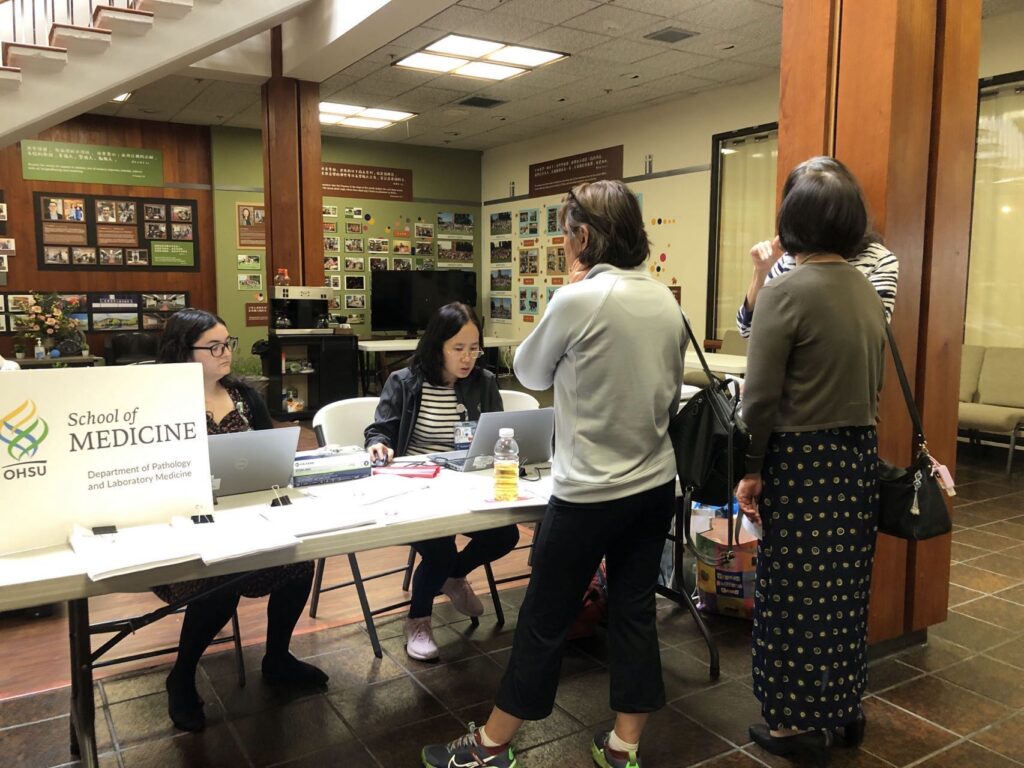

Bridging these language gaps often requires more than translation—it takes cultural nuance. Dr. Zhengchun Lu, a cancer pathologist and resident physician at Oregon Health & Science University, originally from Zhenjiang, China, actively works to meet patients where they are. She communicates with Chinese-speaking patients and adapts CDC and World Health Organization (WHO) materials into formats that resonate culturally. For other language needs, she collaborates with hospital interpreters. “Removing language barriers also removes fear—people feel empowered to get screened,” she says.

To support these efforts, organizations like the American Cancer Society offer multilingual resources through their “Cancer Information in Other Languages” initiative, which provides materials in 13 languages, including Chinese, Korean, Tagalog, and Vietnamese. Making vital information more accessible is a crucial step toward equity in prevention and care.

Limited Awareness, Not Hesitancy

In the first post, Dr. Lu emphasized that many AANHPI patients simply lack awareness about HPV and the need for regular cervical cancer screenings. The same goes for the HPV vaccine.

Dr. Tsui’s research confirms this: “Many people hadn’t heard of the HPV vaccine or didn’t know it helps prevent multiple cancers.”

Adolescents often help bridge the gap. “Teens are more acculturated and read the materials—they’re the ones bringing this information home and influencing family decisions,” she says.

Trusted community messengers also matter. “In many Asian communities, people rely on their aunts, grandmothers, and community leaders,” says Dr. Tsui. “That’s why strong local partnerships are key.”

Navigating a Complicated Health System

Confusion about the U.S. healthcare system can delay screenings and treatment. While many AANHPI communities hold physicians in high regard and prefer care from well-known institutions, accessing these systems—or even getting a second opinion—can be complicated, explains Dr. Tsui.

For patients with abnormal Pap results, referrals to specialists often mean traveling to unfamiliar facilities without language support, creating additional barriers. Demanding work schedules further complicate making and keeping appointments.

To address this, Dr. Lu’s team partners with local groups to host screening events staffed by bilingual volunteers. “Bringing services directly to the community has built trust and boosted participation,” she says.

She also sees promise in HPV self-collection. “It’s not a home test, but it can be offered at outreach events under medical supervision. It’s more private, more flexible, and less intimidating—especially for those wary of pelvic exams.”

Lack of Gender Concordance

“In our Filipino culture, especially among older generations, there’s a belief that you don’t question the doctor—or that traditional remedies are better,” says Arlene. “But many women also feel uncomfortable discussing reproductive health with male doctors and may avoid care because of it.”

Dr. Tsui agrees. “Women are less likely to follow up if they don’t feel comfortable with their provider. In local Asian American communities like our Chinatown, having female doctors can make all the difference.”

Anti-Asian and Anti-Immigrant Sentiment

Lingering fear from the pandemic and rising anti-immigrant rhetoric have also impacted care-seeking behaviors. A 2024 Axios/Harris poll found that 50% of Americans support mass deportations of undocumented immigrants, fueling anxiety in immigrant communities.

“There was definitely a delay in seeking care—not just because of COVID, but because of fear,” says Dr. Tsui. Many in the AANHPI community avoided medical visits due to rising anti-Asian sentiment and concerns about overusing medical resources—or fears that if they left the country, they might not be allowed to return.

This fear compounded the silence around health issues like cervical cancer, which only deepened stigma, Arlene adds. “It’s more important than ever to speak up, share our stories, and help Asian women feel safe and supported.”

Dr. Tsui sees hope in community-driven efforts: “It’s not all doom and gloom. In cities like San Francisco, LA, New York, Chicago, and Atlanta, AANHPI organizations are stepping up. Local clinics and advocates are helping people understand their rights and access life-saving care—just as they did during the pandemic.”

Cultural Beliefs and Cancer Fatalism

In a 2024 American Cancer Society article, Dr. Tingting Zhang, a thyroid cancer survivor, patient advocate, and CEO of ONEiHEALTH, noted: “Some AANHPI individuals may avoid discussing cancer risk, viewing it as a bad omen or personal failure. But cancer is not retribution—it’s biology. And early detection saves lives.”

Cancer fatalism is a well-documented barrier. As Dr. Vu adds, “In my research, Filipino and Vietnamese respondents reported especially high levels of fatalistic beliefs. That mindset can lead to inaction—people believe they can’t change their outcomes, so they don’t engage in prevention. That’s why education is key: the HPV vaccine prevents cancer. We need to make that message loud and clear.”

Let’s Keep Breaking the Silence

At Cervivor, Inc. we believe that every story matters—and every voice can spark change. If you are an AANHPI cervical cancer survivor, caregiver, or advocate, we invite you to join our community. Better yet, share your unique Cervivor Story. (Submit your story here.) Together, we can dismantle stigma, increase awareness, and save lives.