For queer and trans people facing cervical cancer, the challenges go far beyond the diagnosis. They’re compounded by systemic bias, stigma, and a long history of being overlooked or mistreated in healthcare. These barriers are only growing amid ongoing threats to LGBTQIA+ health equity. (Learn more about these challenges—and the work to overcome them—in part two of our Pride Month series. Stay tuned for Monday).

As Dr. Scout, a trans man and Executive Director of the National LGBT Cancer Network, explains, “It’s getting more dangerous to be openly queer in this country right now.” For many, staying safe means staying silent, often at the cost of their health.

That’s why this Pride Month, Cervivor is proud to uplift the voices of Karen North, Anjelica Butcher, Gilma Pereda, and Pixie Bruner—members of our community whose experiences reveal both the challenges and courage of queer cervical cancer survivors. Their stories remind us that behind every statistic is a person who deserves to be seen, heard, and cared for.

Challenging Assumptions: Karen’s Advocacy

Karen, a former nurse from Liberty, Missouri, lives with her longtime partner, who shares the same first name, Karen “Murph” Murphy. Their relationship grew gradually after Karen’s 10-year marriage ended in 2001—a union that brought her a son, Matthew, and helped her recognize her identity as a lesbian. But fear of judgment lingered. “When I was still dealing with custody issues,” she recalls, “I’d deny my relationship with Murph in public if I had to.”

By the time she was diagnosed with breast cancer—and then cervical cancer 18 months later in January 2016—Karen had stopped worrying about court rulings or public opinion. Instead, she leaned on her medical background to stay focused on treatment, not judgment. “I didn’t care what anyone thought. If I felt judged, I’d call it out and find another provider,” she says, adding with a laugh, “I can be a KAREN, in all caps, if I need to be.”

Karen discovered Cervivor in 2017, but it was Cervivor School in 2019 that truly “lit a fire” in her. Today, she leads the Cervivor Pride group and is a vocal advocate for inclusive language. “One of my biggest pet peeves is when people assume everyone with a cervix identifies as a woman,” says Karen.

Conversations with her transgender friend Zeke—who navigates gynecological care as a male-identifying person—have shaped her approach. Karen now avoids euphemisms like “coochie cancer,” opting instead for medical terms or inclusive phrases like “below-the-belt cancer,” which more accurately encompass HPV-related cancers, including cervical, vaginal, vulvar, penile, and anal.

And she credits her Every Cervix Matters hoodie for sparking meaningful dialogue. “A woman came up to me at a restaurant and said, ‘That’s great. Every cervix does matter.’ I got goosebumps,” Karen recalls. “It doesn’t center gender—it centers anatomy and health.”

Transforming Trauma: Gilma’s Awakening

Cervivor Ambassador Gilma, a graphic designer in California, echoes Karen’s message: “It’s called the human papillomavirus—not the women’s papillomavirus,” she emphasizes. “It doesn’t matter your sexual orientation or your gender.”

This perspective led her to vaccinate her then-12-year-old child—now a trans woman—shortly after her cervical cancer diagnosis in 2016. “At her annual checkup, the doctor mentioned the vaccine could prevent cervical cancer,” Gilma recalls. “I said, ‘I don’t care if it’s for girls or boys—whatever it is, my child needs it.’”

Gilma’s cervical cancer journey unfolded alongside a profound personal awakening. Raised in a traditional Catholic household in 1970s Mexico, she followed expected norms—marrying and having a child—despite always feeling “different.” After divorcing at 36 and supporting her child through gender exploration, she began to reflect on her own identity. “Cervical cancer changes your sexual life—a lot. So I stopped worrying about that,” she says. “But it gave me the freedom to express my gender differently.”

A metastatic recurrence at 47, which led her to shave her head after a lifetime of long hair, marked a turning point. “I’ve seen so many women devastated by hair loss—hair carries so much of our identity,” she says. “But for me, I was so happy.” Soon after, she came out to her parents. “I was done trying to fit a mold. Now, I feel comfortable being androgynous.”

Gilma’s advocacy stems from a deeply traumatic experience. During a painful, anesthesia-free cryotherapy procedure to remove precancerous cervical cells, a doctor’s inappropriate touch triggered memories of childhood sexual abuse, causing her to delay treatment for a year. “By that time, it was cancer,” she states.

She credits Cervivor—and years of advocacy training and witnessing other survivors doing “very, very difficult things”—with helping her transform that pain into purpose. Gilma has since shared her story in Spanish-language publications and on a bilingual panel addressing sexual abuse in medical settings, an issue that disproportionately affects her community. “I don’t like the spotlight,” she confides. “But I’ll do it again and again to help prevent this from happening to others.”

Confronting Disparities: Anjelica’s Fight

Anjelica, a small business and nonprofit owner in Baltimore, faced her cervical cancer diagnosis already carrying the weight of multiple identities: Black, queer, caregiver—and often the only one like her in the room. “My cultural background gave me strength and resilience,” she says, “but it also came with silence around topics like sexuality and cancer.”

She quickly saw how deeply healthcare disparities run. “I thought I had great insurance—until I found out it didn’t qualify as catastrophic coverage,” she recalls. Denied care for over a month, she had to pay out-of-pocket to start treatment. “It broke my heart realizing the only reason I made it through was because I could afford to. What happens to the people who can’t?”

For Anjelica, who’s identified as queer since age 13, her cervical cancer diagnosis also brought a realization that “hit hard.” “I was never offered the HPV vaccine—likely because of assumptions about my sexuality,” she shares, referencing persistent stigma and misinformation that overlook how HPV is transmitted: through intimate skin-to-skin contact, not just penetrative sex.

While most of her care team was respectful, certain invasive treatments—like internal radiation—left her feeling unseen and violated. Although the plan was eventually adjusted, the damage had already been done. One provider, referred by her primary doctor, made a lasting difference. “They taught me how to advocate for myself as a Black woman. Most people don’t know how, and it shouldn’t fall solely on us.”

Her support system—her mom, dad, partner, and chosen family—kept her grounded. And with help from a “phenomenal” oncological therapist, she began processing the emotional toll that surfaced after remission. “I didn’t realize how badly I needed community until then.”

Now active in Cervivor and the Ulman Foundation, supporting young adults impacted by cancer, Anjelica shows up in survivor spaces not to seek answers, but to offer hope. “Healing is possible. Remission doesn’t mean going back—it can mean becoming someone even stronger.”

Poetic Resilience: Pixie’s Voice

Pixie, a poet and Cervivor Ambassador from Snellville, Georgia, knows firsthand how gaps in care impact LGBTQIA+ communities. At 26, she was treated for cervical dysplasia, but not tested for HPV. “I wish I had known then what I know now,” she says.

Living with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome and type 1 diabetes, Pixie had always been vigilant about her health. So when she was diagnosed with cervical cancer at 50—with no symptoms—it came as a shock. “I felt numb, contaminated,” she recalls, struggling with the stigma of an STI-related cancer. She underwent a radical hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy. “It was basically the ‘Everything must go! Going out of business sale’ surgery,” she’s described.

Living in rural Georgia, Pixie chose not to disclose her sexual orientation. “When I asked a nurse, ‘What do you define as sex here?’ the answer didn’t reflect my lived experience,” she says. After treatment, a conservative therapist dismissed her concerns about sexuality and body image. “I was reduced to parts—told they were irrelevant because of chemopause and their loss. That I should be grateful to be single. But I was still a sexual being, still human,” she says. “I fired that therapist.”

Cervivor became her lifeline—offering connection, care packages, and space to heal. Her “fairy godmothers,” a married couple, delivered warm meals and encouragement. “Friends are my chosen family and were with me during the long recovery,” she says.

Today, she advocates for inclusive HPV education through Cervivor’s LGBTQIA+ community, and her award-winning poetry—including “Her Kind” and “Medusa With Cancer”—explores how illness reshapes identity. “Cervical cancer took ‘femininity’ and gender away from me in some ways,” she writes. “But my words helped give something back.”

A Call to Action for Equitable Care

While Karen, Gilma, Anjelica, and Pixie each have unique stories, they share a common goal: a more just and inclusive future.

“I want a world where cervical cancer isn’t common,” says Pixie. “Where HPV vaccination is standard, no one is judged for having the ‘wrong’ cancer, self-care is valued, and early detection is affordable and accessible.”

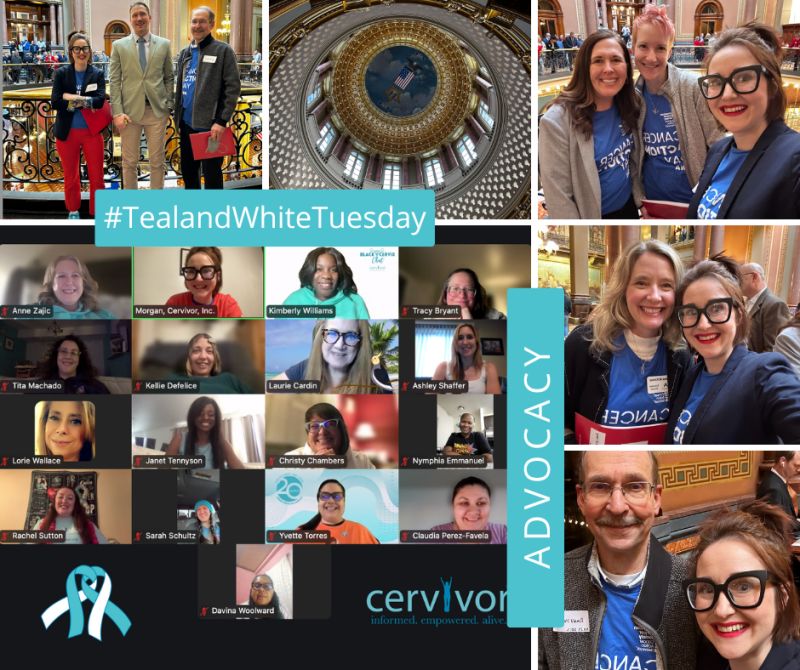

At Cervivor, that vision means making space for everyone. As Community Engagement Liaison Morgan Newman, MSW, shares: “We stand with our cervical cancer community to demand protection and empowerment through prevention. As someone who’s faced this disease, I know the power of vaccines and the importance of accessible healthcare.”

If you or someone you know is part of the LGBTQIA+ community and impacted by cervical cancer, join the Cervivor Pride group (for more information, contact Karen), attend Creating Connections virtual meetups, or take part in local or national outreach.

Support Cervivor’s mission to end cervical cancer by contributing to the ongoing Tell 20, Give 20 awareness and fundraising campaign—honoring 20 years of advocacy, education, and survivorship.